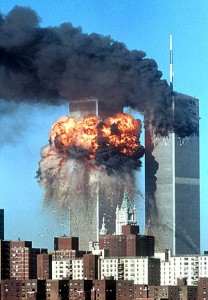

Two years after the 9-11 attacks on the World Trade Center, one more man’s remains have been identified. He is known simply as the 1,638th victim of 2,753. The others are still unaccounted for. Perhaps one day the world may learn #1,638’s name. For twelve years, he had been anonymous, nameless. Not anymore. Family members have been notified. Their fear has been confirmed. They have chosen not to reveal the deceased’s identity. May they all find peace.

Two years after the 9-11 attacks on the World Trade Center, one more man’s remains have been identified. He is known simply as the 1,638th victim of 2,753. The others are still unaccounted for. Perhaps one day the world may learn #1,638’s name. For twelve years, he had been anonymous, nameless. Not anymore. Family members have been notified. Their fear has been confirmed. They have chosen not to reveal the deceased’s identity. May they all find peace.

Others wait. Twelve years after IT happened, wives, husbands, children continue to wait, hope, and grieve. They shed invisible tears. Wives are not labeled widows–not yet. Husbands are not quite widowers. 1,115 names are branded on the hearts of those who treasured and lost them. May they all find love and light.

Days before “IT” happened, my mother dreamed the Statue of Liberty broke apart and sunk. She said: “The Hudson River ran steel-gray; waves crashed as if in a storm. Broken, Lady Liberty floated for a while. Her shattered face bobbed in the violent water. Her Beacon of Promise had disintegrated. And then the whole thing drowned.” My mother’s dream, like hundreds of others she’d recounted over the years, was disturbing. And mildly prophetic.

Days before “IT” happened, my mother dreamed the Statue of Liberty broke apart and sunk. She said: “The Hudson River ran steel-gray; waves crashed as if in a storm. Broken, Lady Liberty floated for a while. Her shattered face bobbed in the violent water. Her Beacon of Promise had disintegrated. And then the whole thing drowned.” My mother’s dream, like hundreds of others she’d recounted over the years, was disturbing. And mildly prophetic.

What’s your story? Have you told anyone? Do you have one? Do you remember what you were doing that Tuesday morning in September when the world screeched to a halt? Were you on your way to work, only to discover that your workplace no longer existed? Do you still wake up in the middle of the night, calling out the name of someone who disappeared under mountains of rubble, fire, and steel? Do you keep those memories in places where no one–not even you–can find them? Had you dreamed about Liberty drowning, too?

Depending on where your birth date falls on the timeline of history’s many catastrophes, “IT” has a different meaning: The Parsley Massacre, Pearl Harbor, The Korean War, Viêt Nam, the Sharpeville Massacre, JFK, MLK, and RFK’s assassinations, the Challenger explosion, Iran-Contra, Exxon-Valdez, Kosovo, Columbine?

What were you doing when American Airlines Flight Number Eleven flew into the North Tower, hurling unsuspecting victims into a death so certain and senseless that the world shivered with shock?

What were you doing when American Airlines Flight Number Eleven flew into the North Tower, hurling unsuspecting victims into a death so certain and senseless that the world shivered with shock?

Were you having breakfast? Pancakes? Leftovers from the Chinese place around the corner? Were you arguing with a friend about a football game? The Giants? The Eagles? The Redskins? What were you wearing? Had you awaken with a sense that some strange thing would happen that day? I didn’t.

It began as an ordinary Tuesday. I performed the same morning rituals: Showered, dressed, walked to the Silver Spring Metro station; waited for the Red Line Train to take me to Farragut North in DC. Got on the train seconds before the door shut. Sat where I wouldn’t have to listen to someone’s music through his/her earphone.

When I reached my office building in Washington, DC, the secretary took me by the wrist, whispering urgently: “Have you heard?”

“Heard what?” I had been on the Metro for thirty minutes. I heard nothing but the grumble of trains and the mumble of disgruntled employees. The secretary was shaking. Her eyes had become slits, as if she was afraid to look through them.

“You don’t know?” Trembling hands cupped over her mouth.

She pulled me into the nearest office in the super-sized international law firm. Dozens of fresh-out-of-school attorneys, seasoned counsels, custodians, secretaries, paralegals, mail distributors, and powerful partners waited–together, this time. The usual hierarchy had shifted. Brotherhood reigned supreme. Then came the second airplane.

And wings sprouted between my shoulder blades.

I flew to my own office to call my sister. She had a job in Capitol Hill. “Get out of DC,” I yelled. “DC is next.” It was just a guess.

I telephoned my husband. He’d heard the news on NPR. He said he’d been trying to call me, but his phone kept dying. “Drive toward DC,” I said. “I’m walking. I’ll meet you half-way.”

The end had come. Sky had become Earth. Light had turned to darkness. And darkness enshrouded us. Was this some kind of war? My husband and I did not question what was happening. We knew only one thing: we would find each other, or die trying.

I would have walked a thousand miles to reach him, knowing that he would have done the same for me. He was fewer than twenty miles away, but he might as well have been on Pluto. Before I left the building however, I had one very important task to get done.

First, I stopped by a friend’s office—an attorney with a heart so big you would have thought she fell into the profession by accident. “If you need anything,” I told her, “come to our apartment. We have water, some food, and we’re not in DC.” My friend said she would, if it she needed anything.

The newly-built office building where we worked was located in the heart of Washington, DC. The glass windows were spotless; miles of steel glinted with sun-rays that ricocheted off other high-rises filled with high-powered executives who must have felt powerless against the unseen thing that continued to crash planes into their American dreams.

The newly-built office building where we worked was located in the heart of Washington, DC. The glass windows were spotless; miles of steel glinted with sun-rays that ricocheted off other high-rises filled with high-powered executives who must have felt powerless against the unseen thing that continued to crash planes into their American dreams.

“I don’t think I’ll be in today,” one of the attorneys called his secretary to say. “I think I just saw a plane fly into the Pentagon. I must be insane. Yes . . . No, I’m not crazy. Sh!t. I should go back home. Yes, a plane did hit the. . .Pentagon. . .Fire. . . . Sweet Jesus!” And then the phone went dead.

Fear clogged the air. Leather soles became roots that locked people in place. Legs had become heavier than stones, making it impossible to run. Briefcases, expensive purses: drop everything. Run. But to where?

If New York and DC have been hit, where would anyone go? Screams echoed around us. Voices shouted:

“The Capitol Building went down.”

“They blew up Pennsylvania Avenue.”

“It’s World War III.”

“I always knew aliens would destroy Earth one day.”

“I heard Nuclear bombs are next. . .”

On and on, wild stories swarmed like mosquitoes that stung our ears. The stories stung our faith. Our lives.

The truth would not come for some time. For now, wild imaginings ruled. One thing was real, though: The Metro system ran underneath our buildings. Our feet. Sweet Jesus, indeed!

“The Metro is next,” someone screamed. Brown, blue, grey and green eyes were studded with colorless fear. We would die. All of us. Still, I held on to one fact: my husband and I would find each other.

Or die trying.

There he stood—the colleague for whom I had very strong feelings. I would tell him today how I felt. Why not? The world was ending. This would be my final opportunity.

My husband knew how I felt about this other man; he understood. Most of my friends knew. Everyone but the man knew how I felt about him. I had to tell him. This could not wait.

There he was, waiting, catatonic—frozen in the stairway, a confused look on his face. He was not sure whether to run upstairs or down.

The world had spun him like a top. His right was now his left, and vice versa. This was Armageddon, the final chapter in our book of life. This was the Apocalypse. I would tell the man how I felt.

“I hate you!”

How long had I wanted to let him know the secret I kept so well hidden behind smiles and pleasantries?

“I despise you. Do you understand me?” I breathed, relieved. Something shook loose inside of me. I was free at last. Free to live. Free to die.

“What?” the man looked at me, shaking his head. Clearing the fog a little. “What did you say?”

I appreciated the opportunity to repeat what I’d wanted to say for so long: “I hate you. I have always hated you. You’re a freakin’ creep. An a-hole. You get on my nerves. Always have. The world is over. See you in space, jacka$$. Tootles, B!tch. Butthead! Salud, MF!”

He squinted hard, and tried to lift the legs that were supposed to carry him away from the whir of madness. I wasn’t sure if he’d heard me correctly, but my fantasy had materialized enough. I dusted my wings and flew out of the building.

I tried to call my husband again. The phone was useless. Phones would stay dead for many days, but my husband and I had already talked. We had plans. We would find each other somehow.

I tried to call my husband again. The phone was useless. Phones would stay dead for many days, but my husband and I had already talked. We had plans. We would find each other somehow.

Thousands of workers spilled into the streets. K, 18th, 19th, I, Connecticut: Farragut Square, making a human gridlock.

I began a strange dance—a macabre waltz with the unknown thing which we thought would bury DC under heaps of rubble. This was our Pompei. Our Machu Picchu. So, I danced: One step to the right, one leap to the left. Sprint to the right, zig to the middle of the street.

Soon, many others began to do the same. Couples held hands, and danced a little dance with death. Surely something would explode from underneath and swallow the street and the people on it. We might be able to avoid being sucked down, if we danced well enough. Standing in place was like begging for the bad thing to pull us under.

I continued to dance-walk. I tried the cell-phone again. Nothing. Other people slapped their own cellular phones; they tapped their ear-pieces, crying out in desperate tones: “Hello? Are you there? Hello? Honey, can you hear me? Sweetheart? Hello?”

A man followed me like a shadow. When I leaped to the right, he did too. When I ran, he ran. He seemed even more lost than the rest of us. He couldn’t have been more than twenty. One foot was bare on the asphalt. He wore one stark white sock on the other. White t-shirt. Khaki pants. He had curly blond hair. Thin, angular face. Small mouth. Cloudless sky-blue eyes. Innocent-looking chin. “Why are you following me?” I wanted to know.

A man followed me like a shadow. When I leaped to the right, he did too. When I ran, he ran. He seemed even more lost than the rest of us. He couldn’t have been more than twenty. One foot was bare on the asphalt. He wore one stark white sock on the other. White t-shirt. Khaki pants. He had curly blond hair. Thin, angular face. Small mouth. Cloudless sky-blue eyes. Innocent-looking chin. “Why are you following me?” I wanted to know.

“I’m a student. Georgetown. Law,” he said quickly. He reeked of old money. Old, old money–wealth and position that meant nothing now that he was in the street with the rest of us. He said his apartment was too close to the White House. He feared he would be hurt. Killed. The apartment was too close. He needed to get away from DC, he said. “I don’t have any family here. Can you help me?” Tears welled in his blue eyes.

How exactly was I supposed to help him? What did he think I would be able to do?

“I have to keep walking,” I told him. “My husband is coming to get me. We live a ways from DC. You could stay with us. We have some water. A little food. You could wait there until you reach your people.”

“Your husband won’t come to get you,” he said. “Traffic isn’t moving. Nothing is moving. Look around you. We’re as good as dead.”

“He’ll be here.”

On cue, my husband shouted for me to get in the car. “Hurry,” cried out.

“This man is lost,” I said to my husband, indicating Georgetown Law Student. “He doesn’t have anyone. We have to help him” I said.

“Let’s go,” my husband answered. He knew me. My decision was final. We would help the stranger. Or die trying.

I sat in the passenger seat. The stranger sat directly behind me. “ We live in Silver Spring. We’ll probably be okay there for a few days,” I said.

Another thought occurred to me suddenly. So,I asked the question I should have asked long before: “How do we know you’re not one of of them? How do we know you’re not going to kill us?”

“I’m not one of the bad people,” he said, and I believed him. Of course, being me, I had to add a little Haitian pikliz to the situation: “Next time you see black people in the street, you’ll know we’re not out to get you,” I said. “On top of that, I’m from Haiti. Don’t forget I come from Haiti.” I’m still not sure how that was supposed to change our predicament, but I said the words. I come from Haiti. I am Haitian.

“Of course, Haiti,” he said. “One of my best friends from law school is. Haitian.”

Right.

Georgetown Law Student stayed with us for a day or two. By that time, we had learned the world would not end. The bad people had a name: Terrorists. Our guest was not one of them.

It was Hatred—like a Stealth aircraft—that had hovered over us, waiting to strike. Hatred stayed busy that September morning, busier than those diligent workers who kept right on striking keys on ergonomically-correct keyboards.

It was Hatred—like a Stealth aircraft—that had hovered over us, waiting to strike. Hatred stayed busy that September morning, busier than those diligent workers who kept right on striking keys on ergonomically-correct keyboards.

Hatred was to blame.

Days went by before we returned to our offices. Days before I had to face the man to whom I had revealed my true feelings of hatred. He and I would laugh about it afterwards. We would become good friends. He married and changed his mind about DC. He is now a preacher at a church Down South. He was a nice man, I came to learn. He was one of the good guys—a regular guy, like all the regular guys and gals who came to the Millennium Building to work everyday.

How relieved we had been when we reached our apartment in Silver Spring! I remember thinking that if Death had come to claim us, it would have found us helping a total stranger. He would have known that brotherhood–not fear–reigned supreme.

The student from Georgetown Law sent us a post-card months after the 9-11 attacks. He wanted to thank my husband and me for our kindness. We still have that post-card somewhere.

It’s you. You’re the one. You are the miracle a stranger’s been praying for. He doesn’t know you. You don’t know him. But he is there on a sidewalk somewhere, praying that you would give him a chance–a second chance. After all, it’s Thanksgiving. You have food on your table. Lots of it. By morning, the cranberry sauce no one even touched will be in a trash bag. The pasta salad won’t keep. As for the turkey, you’ll have wings and thighs coming out of your ears by Black Friday. Still, the stranger prays for the miracle. You are the miracle, but you don’t believe this. You barely have enough to take care of your own household. You’re not the one.

It’s you. You’re the one. You are the miracle a stranger’s been praying for. He doesn’t know you. You don’t know him. But he is there on a sidewalk somewhere, praying that you would give him a chance–a second chance. After all, it’s Thanksgiving. You have food on your table. Lots of it. By morning, the cranberry sauce no one even touched will be in a trash bag. The pasta salad won’t keep. As for the turkey, you’ll have wings and thighs coming out of your ears by Black Friday. Still, the stranger prays for the miracle. You are the miracle, but you don’t believe this. You barely have enough to take care of your own household. You’re not the one.

You want only to feel useful again. You need to care for your children again. The fast food joint’s manager said you were overqualified. And weird. You knock on doors, offering to cut unruly grass. You walk Pitt bulls and poodles. Anything for a dollar. Maybe 10!

You want only to feel useful again. You need to care for your children again. The fast food joint’s manager said you were overqualified. And weird. You knock on doors, offering to cut unruly grass. You walk Pitt bulls and poodles. Anything for a dollar. Maybe 10! Plumbing. . .not yet either. You wouldn’t pretend to be able to fix leaking pipes. But you can patch a little water damage on the ceiling. Hang some drywall. Drill a couple of two-by-fours down and build a wall where one hadn’t been before. You’d always been a master at building walls. Walls like the one the wife put between you and the kids. Walls like the one keeping you apart from the job you held twenty years. 20 years of loyalty that meant nothing to the boss who had security escort you out. Those you past–friends, colleagues: no one said a word. No one wished you luck. You became the stranger you had always been.

Plumbing. . .not yet either. You wouldn’t pretend to be able to fix leaking pipes. But you can patch a little water damage on the ceiling. Hang some drywall. Drill a couple of two-by-fours down and build a wall where one hadn’t been before. You’d always been a master at building walls. Walls like the one the wife put between you and the kids. Walls like the one keeping you apart from the job you held twenty years. 20 years of loyalty that meant nothing to the boss who had security escort you out. Those you past–friends, colleagues: no one said a word. No one wished you luck. You became the stranger you had always been. So, you see, this week is not good for me at all. Let’s shoot for next weekend. You could start to build the wall then. I need it done before Christmas. Guests are coming. And that big room upstairs can easily be made into two bedrooms. All we need is a wall. I’d build it myself, but the wife needs my attention. And the kids…well you know how that is. Do you have children? No. . .You don’t look like the type. Well, let me tell you: you’re lucky. A bachelor. I remember those days myself. Great times, right.

So, you see, this week is not good for me at all. Let’s shoot for next weekend. You could start to build the wall then. I need it done before Christmas. Guests are coming. And that big room upstairs can easily be made into two bedrooms. All we need is a wall. I’d build it myself, but the wife needs my attention. And the kids…well you know how that is. Do you have children? No. . .You don’t look like the type. Well, let me tell you: you’re lucky. A bachelor. I remember those days myself. Great times, right.