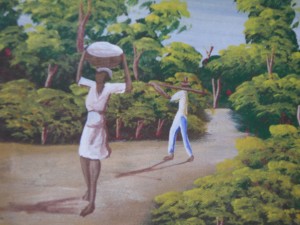

As the plane made its final descent, the features of the island became more distinct. There were many scars on her face now. Deforestation had claimed many acres. From the north to south, east to west—like a massive cross branded on the country’s back, destitution had seeped into the soil, and rooted itself so deeply that nothing but poverty would grow. Gone was the majestic fir that once crowned the mountains. Silent were the songbirds about which many fables had been spun. The ancestors must be grieving now, I thought. But where the island was still green, the Garden of Eden might have withered with envy.

As the plane made its final descent, the features of the island became more distinct. There were many scars on her face now. Deforestation had claimed many acres. From the north to south, east to west—like a massive cross branded on the country’s back, destitution had seeped into the soil, and rooted itself so deeply that nothing but poverty would grow. Gone was the majestic fir that once crowned the mountains. Silent were the songbirds about which many fables had been spun. The ancestors must be grieving now, I thought. But where the island was still green, the Garden of Eden might have withered with envy.

When the pilot announced that 85 degrees awaited us on the ground, I noticed a legion of pale-skinned soldiers leading seven Spaniards away. They had bound them together. The Arawak Indians had disappeared from my reverie. Hispaniola had become a colony; France was the mother country. Inside the airplane, passengers shifted in their seats with restless anticipation. Between the aisles, I saw a hundred Dahomeans layered on human shelves, across the belly of a nameless ship. They writhed in despair. When the plane touched the runway, a tall black man had jumped to his death in the open sea. A woman quickly followed him. I walked down the aisle toward the plane’s exit door. The Africans were cutting sugar cane now, in a vast field without a horizon. Sweat drenched the rags that sheathed their fate.

When the pilot announced that 85 degrees awaited us on the ground, I noticed a legion of pale-skinned soldiers leading seven Spaniards away. They had bound them together. The Arawak Indians had disappeared from my reverie. Hispaniola had become a colony; France was the mother country. Inside the airplane, passengers shifted in their seats with restless anticipation. Between the aisles, I saw a hundred Dahomeans layered on human shelves, across the belly of a nameless ship. They writhed in despair. When the plane touched the runway, a tall black man had jumped to his death in the open sea. A woman quickly followed him. I walked down the aisle toward the plane’s exit door. The Africans were cutting sugar cane now, in a vast field without a horizon. Sweat drenched the rags that sheathed their fate.

As I reached the door of the plane, I saw clusters of Haitians in the same forest where the Taino had once walked, just as I had read in the history book as a child. It was 1803; the drums of revolution serenaded the midnight moon. History would be made. I was grateful that my dark sunglasses would mask the torrent of emotions that had suddenly flooded my eyes. I descended the stairs; something inside began to unravel.

When my feet touched the soil, it occurred to me with absolute certainty that the person I called myself was but a remnant of a former self. And that person was was lost now. The heart with which I experienced the bittersweet joy of going home again was fragmented, too—and felt as if it were beating in someone else’s chest. The mind that reminded me that there was no such thing as going home again throbbed with random thoughts which were as alien to me as I would always be to the U. S. Like a fruit plucked from its branch too soon, I sought to achieve ripeness in a foreign place. Ripeness, being inevitable, came in an unnatural manner, and deterioration followed with a double quickness that left my spirit in an exaggerated state of rot.

I strayed from the line of passengers headed for Customs, to catch my breath. I closed my eyes and let the heat sink into my skin. A tropical breeze reversed the frantic rhythm of my heart, and I felt those fragments of my lost self begin to merge. A sense of totality came.

Inside the airport I found the large bag I had brought and dragged it behind me like a dog dragging its tail. The cry of babies, frustrated from the four-hour trip, reverberated inside my head. Older children invented games to entertain themselves while their parents waited for their luggage. Above the din of suitcases screeching across the floor, the blades of a ceiling fan stirred the heat with the patience of eternity.

An older woman, who looked positively regal in her wheelchair, drew a lungful of smoke from her cigarette. The air around her unleashed my own craving for a smoke. I thought about asking her for a cigarette, but even if she had offered one (which she would not), I could not accept it. In Haiti, I would not surrender to the habits I practiced on U. S. soil: I would never smoke in public; I would not look my elders in the eye; I would not laugh too loudly.

An older woman, who looked positively regal in her wheelchair, drew a lungful of smoke from her cigarette. The air around her unleashed my own craving for a smoke. I thought about asking her for a cigarette, but even if she had offered one (which she would not), I could not accept it. In Haiti, I would not surrender to the habits I practiced on U. S. soil: I would never smoke in public; I would not look my elders in the eye; I would not laugh too loudly.

I would not wear yellow, for my mother said that yellow is the color of treason; and girls who loved their families the way she said I didn’t, would never be caught dead in a yellow dress.

I would not wear red, for red is the color of sex, passion.

I would not wear black, that is the color of death.

I would not wear white, for white is the color of the undead.

I laughed inwardly and told myself that perhaps I should wear just my black skin, until I remembered that nakedness was the very costume of devils.

I worried about the rules I had forgotten about how a Haitian woman ought to behave. I resolved to remember those rules when I returned to Washington, DC.

I stood in the corner, unwilling to move; even though I knew my cousins were waiting for me outside. I had not seen them in years. They were seven and eight when I left home. And it occurred to me that I had, in fact, forgotten their faces.

I stood in the corner, unwilling to move; even though I knew my cousins were waiting for me outside. I had not seen them in years. They were seven and eight when I left home. And it occurred to me that I had, in fact, forgotten their faces.

I leaned against the wall and waited, stealing glimpses of the faces around me; they were afraid. The newspapers had told them to be afraid: Haiti was not safe.

Fear was in the wild wave of their arms. They had read it on the Internet. They had seen the signs posted at departure gates telling them that Haiti was Unstable. UNSTABLE. Unsafe. Death. Kidnapping. Aids! And I was afraid.

Perhaps I should tell the stewardess that I had changed my mind and wanted to go back in the same plane that had brought me. I’d call my cousins to tell them how sad I was to have missed the flight. They would never know that I was only too terrified by the sounds coming from outside the airport: the yelling, the crying, and the begging.

No one would ever know how I really felt. I hadn’t been there in 200 years, what would 200 more matter?

“Going someplace fun?” my boss had asked when I requested time off for vacation. “Home,” I had said.

“You mean Haiti?”

“Yes,” I answered.

“My husband and I have been to the Dominican Republic several times,” the woman continued, “but I’ve never made it to Haiti. I’ve seen documentaries and pictures, that sort of thing. Your country is really destitute, isn’t it? The Post had an article about it last week. Is it true there are no trees left?” She did not wait for an answer before continuing. “Haiti is the poorest country in the Western Hemisphere. Why would you want to go there now? Is there some emergency?”

“My husband and I have been to the Dominican Republic several times,” the woman continued, “but I’ve never made it to Haiti. I’ve seen documentaries and pictures, that sort of thing. Your country is really destitute, isn’t it? The Post had an article about it last week. Is it true there are no trees left?” She did not wait for an answer before continuing. “Haiti is the poorest country in the Western Hemisphere. Why would you want to go there now? Is there some emergency?”

“No emergency.”

“Well, then, why don’t you go some place less unstable? The Dominican Republic has very nice beaches in the North. You must go there. It’s hard for me to believe that Haiti is on the same island.”

“Haiti is my home,” I said.

To read the contribution in its entirety, visit The Caribbean Writer. Volume 16 (2002)