When, as a young man, my body began to utter its first words of puberty, my mother had accepted into our home the daughter of a villager with whom we’d had a business relationship. At the time, my family owned at least two businesses in Jeremie.

Rosanna, more ravishing than an orchid, came from the Department of Grande-Anse. We were approximately the same age; and through the abyss in her eyes, I detected she held some affection for me.

During that time, however, I wanted only to become a priest. The priesthood had seemed the ideal path by which to help my compatriots. As my family’s wealth grew, thoughts of helping the poor dominated my life.

I awoke early each day to serve at mass. Sexuality– a mortal sin, according to the priests–did not enter into my life’s vocabulary at all. Still, my friendship with Rosanna intensified.

I would gather clusters of pleasure from the sound of her voice. I enjoyed hearing her talk about her life in the countryside. I wanted to go with her, at least for a few weeks—wherever she would have taken me.

—————

In the compound where we lived—in Bordes, there resided a young man called Senerè, the son of the caretaker.

Senerè swore his life would end without Rosanna in it. He needed her to breathe. Yes, he was deeply in love, even if Rosanna was not interested. Even if she wanted nothing to do with him.

One Sunday afternoon, when everyone had gathered on front porches and under shade trees for a détente, a little voice inside told me to return to the compound. I did not ignore the voice. I would always be grateful for that decision.

When I reached the compound and heard a most disturbing scream, I ran to investigate. There, in a dark room, I found Senerè. A violent look in his eyes. He held his weapon in one hand, preparing to violate young Rosanna.

Rosanna, who had dressed so prettily in her Sunday outfit, stood defenseless against Senerè’s weapon. Had I not come when I did, the crime would have taken place. It would have been too late.

When Senerè saw me, he bolted like an animal and escaped.

Two rivers sprang from Rosanna’s eyes.

————-

When she put her arms around me to thank me, something stirred inside of me—a sensation I had never known before and have never forgotten. Out of respect for this girl and for God, I quickly separated myself from her physically, but promised to always protect her.

Rosanna had become my oasis in the desert. We became inseparable—in every sense—for more than 2 years, until I had to leave Jeremie to complete my studies in Port-au-Prince.

Three years afterwards, when a group of classmates and I went to celebrate the end of a difficult exam at a cafe, I noticed a girl who reminded me of Rosanna. The more I stared, the more I knew: Yes, it was Rosanna.

She had migrated to Port-au-Prince; she wanted a better life, too. Rosanna and I quickly resumed our friendship. Everyday she would cook for me at the place where she worked. I would take her to the cinema and for long walks along Champs de Mars. It was there that a pack of Tonton Makoutes attacked and nearly killed me. I managed to get away, and hid for days at Rosanna’s place. This time, it was she who had saved my life.

Time flowed downstream, as usual. Now and again, it unfolded its imposing body, and threaded itself through the eye of history, always trying to spare Haiti the brutality of dictators. . .

I was a writer. I had a voice. I chose not to be silent. It was not long before I was forced to join the long list of exiled compatriots.

———–

I spent more than 25 years in exile before the dictatorship of Jean-Claude Duvalier collapsed, and I was able to go home again.

It was April, 1996 when I reached Haiti. The first thing I did was search for Rosanna. I needed to find her. I had failed to protect her as I promised her I would. I asked, but no one could tell me her whereabouts.

Even though the dictatorship had collapsed, times were still volatile. There were coups after coups; assassinations on top of assassinations. The kidnapping situation was at its highest. Each time one friend asked about another, kidnapping would be part of the answer. Those were volatile days, indeed: Innocent people, like the journalist Jacques Roche, lost their lives daily. Women were violated in the presence of their husbands and children. The city of Port-au-Prince had become a prison. People barricaded themselves in their own homes. Everyone feared being kidnapped.

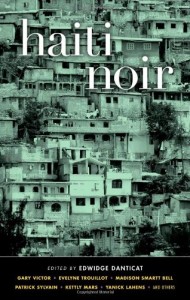

For this reason, when the celebrated writer, Edwidge Danticat contacted me regarding the Haiti Noir anthology, the first subject that came to mind was a kidnapping. I used that scenario to introduce Rosanna, and pay overdue homage for the role she played in my life. This is how, also, in the year 2011, news reached my ears that my dear Rosanna had died in Port-au-Prince. They tell me she had a son. It was good to know she did not live (and die) alone.

They tell me, also, that Rosanna’s son is a priest in the Grande Anse. Perhaps, I will meet him some day. I would love to know more about how Rosanna lived–this actress who played the greatest role in my life.

I want the readers of Haiti Noir to know the original source of my story’s inspiration—although I spun the character in such a way to isolate those facts that don’t quite fit in the domain of “creative fiction.”

J-R Large, July 2011, New York

(English translation of J-R Large’s “Synopsis of Rosanna” by Katia D. Ulysse)