Humor me, please. Here I will list my fears of the “Dark Island” (a play on the infamous “Dark Continent” references that were so prevalent in American literature & film). And humor is the best way to deal with what I consider warranted concerns about returning to Haiti for the second time (as an adult), other than writing about it as fiction, YA fantasy/supernatural horror to be exact. After all, as Wrinkle In Time author, Madeleline L’Engle stated, “If it’s too complicated for adults, write it for children.”

(And Griot as in the keeper of culture and teller of history, not the fried bits of pork that’s so popular in Haitian cuisine, but pun is intended).

At long last, after several attempts, I leave for Haiti on a research trip as part of the grant I won from the Speculative Literature Foundation. Yes, right after Hurricane Sandy ravaged through the little island, and ironically New York City as well. There’s no denying that hurricanes are forces. And I’ll be retracing Sandy’s path.

There’s so much more I can say about this because I’m extremely critical about these things. But given my environment where ideas and events are not supported by any sort of spiritual cosmology (a hurricane, the force of Oya, guardian of cemeteries, joins forces with Gede, also the guardian of cemeteries, change and transition—what does that mean?), my fears are simply just that, fears.

I’m going to Haiti to research my novel in (perpetual) progress. Initially, I wanted to travel between Port-au-Prince and Santo Domingo, DR and visit the bateyes, Massacre River, Sonia Pierre’s organization, etc. Yes, a hefty journey (and Sonia Pierre unfortunately passed away last December). But ultimately, the DR/Haiti relationship is not the story I’m telling.

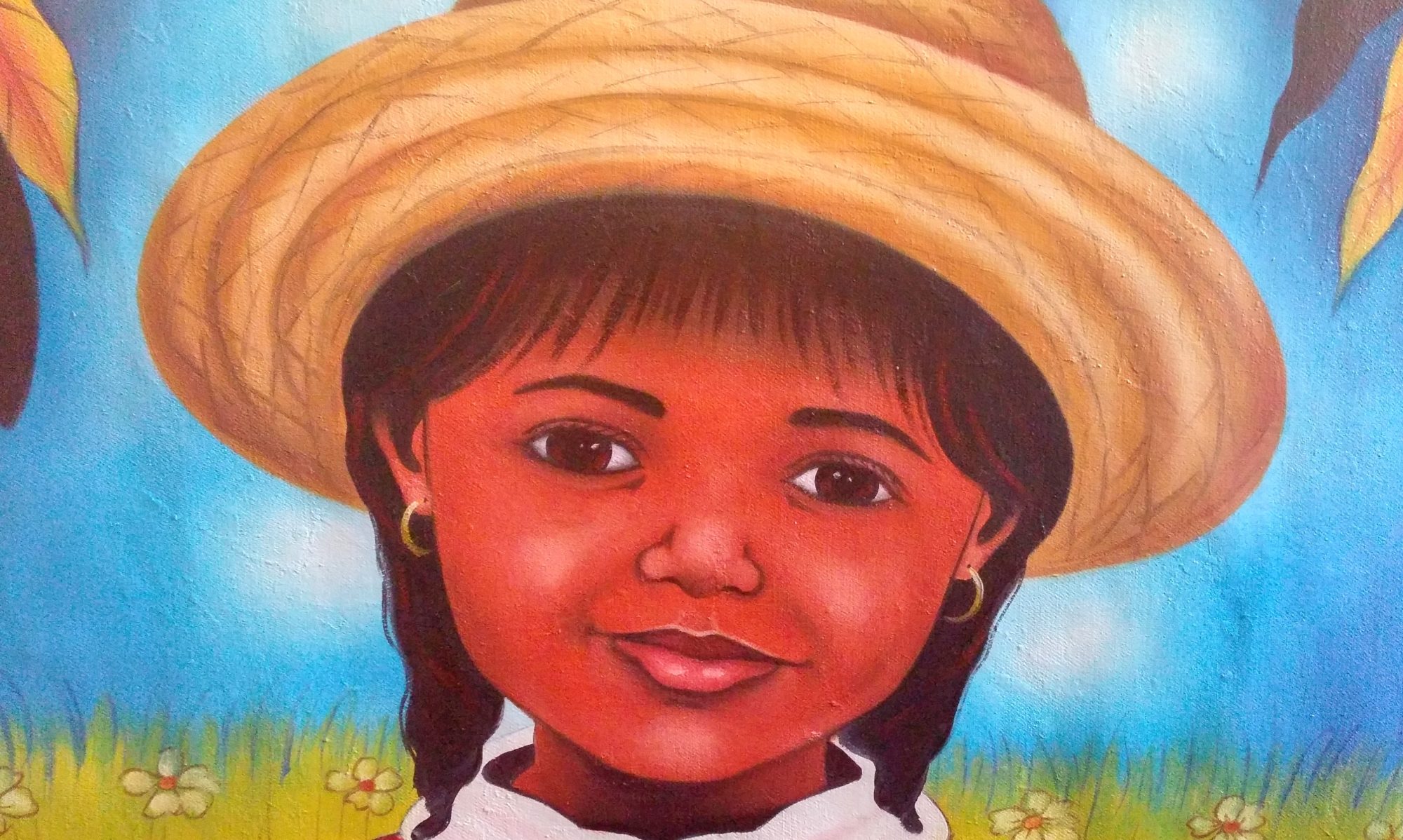

My story is of Haiti’s magical world, this island of Kiskeya and the unseen spirits that aided its people through a successful revolution, self-governance, preserving culture and tradition, and in spite of all this, according to the media, continued political corruption, violence, and “suffering.” The worst photos being circulated of Hurricane Sandy’s aftermath are of Haiti. So it makes absolute sense to investigate how Haitians view death. So Gédé it is. Or Féte de Morts. Day of the Dead. All Souls Day. The ancestors.

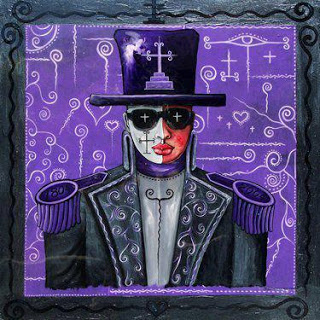

1. Yes, Gédé looks…scary. Skeletons and coffins and lewd dancing and alcohol (spirits). The epitome of all the negative representations of Vodou. Yes, I fear it a bit. Not for any of the obvious reasons, but because I have an intellectual understanding of what death means in a place like Haiti. By celebrating Gédé, we honor those who passed. But in my little pre-occupied mind, I can’t help but to think of those who lost their lives violently, without cause, and whose death could have been prevented by simple things like adequate nutrition, clean water, and decent shelter. When those spirits are called forth from their underworld homes, are they bitter? Angry? Do they want vengeance on the living? And I’m not talking just a few here, but the hundreds and thousands who have perished in one single moment—a deadly hurricane, a capsized boat, the recent earthquake. Even those who lost their lives in the Haitian Revolution and wander through Haiti over time as ghosts to witness what has become of the nation they fought for—they must be pissed. But part of me also understands that these preconceived notions of what Gédé actually represents have been instilled in me since childhood, the media, and other Haitians. There’s science in Vodou and every other indigenous cosmology and mythology. And if I’m to represent it in my writing, I’m careful not to do what so many other non-Haitians have done with Vodou in fiction. Hence, a research trip right into the heart of Gédé. His day is celebrated from November 1st and the following days. His colors are purple and black. Gédé in Brooklyn is one thing, but Gédé in Port-au-Prince is a whole other mambo-jambo. Yeesh.

2. Yes, I have a wee bit of a fear of being kidnapped. I’m a writer so I can envision just about every worst case scenario within a fleeting moment. This is why I write speculative fiction. I ask, what if… and then I’m the hero of my own adventure. But the biggest news coming out of Haiti is the arrest of one of the most notorious kidnappers (well, an orchestrator of kidnappings) in the country. My sister was insistent on letting me know that he was a mulatto and those who were kidnapped were of the same elite class. Meaning, kidnappers will want nothing to do with me. Good. But, still. I don’t want to be completely naïve. I’ve witnessed desperation in Haiti. To walk out of the airport and be greeted by the opened extended hands of children is mind-boggling.

3. My mother was supposed to come with me. But she’s one of the many, many Haitian immigrants who fear returning home—or they only go back for funerals. Not even weddings (My cousin is getting married, so I’ll be seeing some of my extended family for the first time since I was 4 years old. They will have lots of stories for me.) Her fears are different from mine, of course. My mother was devastated after the earthquake, but yet, she refuses to go home. Haiti is no longer home. The landscape has changed, there are memories she buried there. And here I am trying to excavate them all—asking all the wrong questions, digging and prying. I’m completely blown away by what I’m finding in my research of the Duvalier years—the Tonton Macoute, the overwhelming fear, the unwarranted assassinations, the opulence of the Haitian ruling class, the economic divide. I totally get my mother. And this adds to my fear. I know that I lose a little bit of freedom whenever I step outside of the U.S. I don’t have the freedom to go to Haiti and ask just about anyone about Vodou. If I do, it’s under the guise of being a journalist. And I fear not having enough money to hand out to everyone who offers any bit of information. There’s an expectation that if you’re coming from the U.S., you’re in Haiti to offer help. But I’ll be taking for now. I would have taken all these stories from so many voices, and not have anything to offer in return.

4. I fear not having my story heard. And this wouldn’t be my story alone. I’d be pulling from memories and fears that are not necessarily my own. The memories of my family when they passionately talk about Haiti and Haitian politics. The fears of those in Haiti who truly believe that there’s no hope for their nation. The images of Haitia re true and false, warped and precise. There are contradictions, dichotomies, dualities that coexist like Marassa. See, there’s a loa for just about every concept. That’s what I have to offer, I guess. Another perspective on the spiritual science all Haitians have inherited. My own writing.

5. I hope that new stories are enough. I fear that few will recognize it as such. New stories. A new script.

And here’s a bit of news that I think acts as a catalyst for this new narrative:

From the Policy & Standards Division of the Library of Congress:

“PSD was petitioned by a group of scholars and practitioners of vodou to change the spelling of the heading Voodooism. They successfully argued that vodou is the more accurate spelling, and that the spelling “voodoo” has become pejorative. The base heading was revised to Vodou on this list, and all other uses of the word “voodoo” in references and scope notes have also been revised.”

Spearheaded by Vodou scholar Dr. Kate Ramsey.

Republished with permission from the author.