Chak Moun Gen ti Istwa Ayiti pa yo.” Over ten years ago, an elderly woman said those words that continue to mark how I understand Haiti and want to express and explain it. Indeed, everyone has his own little history/story of Haiti. In the aftermath of the earthquake, from far away, I mourned yet wondered what would happen to those with stories/histories that were made on that tragic day.

Chak Moun Gen ti Istwa Ayiti pa yo.” Over ten years ago, an elderly woman said those words that continue to mark how I understand Haiti and want to express and explain it. Indeed, everyone has his own little history/story of Haiti. In the aftermath of the earthquake, from far away, I mourned yet wondered what would happen to those with stories/histories that were made on that tragic day.

Upon my first post-quake visit that Easter, I quickly realized that so many people wanted to tell their stories. Everyone I asked had something they wanted to say. I returned from Haiti with a grandiose idea for a country-wide oral history project that would document the experiences of anyone who wished to share their stories, however they wanted to tell them. These I imagined would be gathered using all sorts of media to be kept both locally in (new) community centers that could serve as historical societies as well national archives.

My interest was in creating a project around which community organizing could be reinvigorated. My motive remained a need to document the fact that everyone would have their version of a January 12th story. Each version would reflect so much about who we are, where we are (where we were on that tragic day); what kind of resources we have, how we handled challenges, what united us, and, of course, what divided us.

My interest was in creating a project around which community organizing could be reinvigorated. My motive remained a need to document the fact that everyone would have their version of a January 12th story. Each version would reflect so much about who we are, where we are (where we were on that tragic day); what kind of resources we have, how we handled challenges, what united us, and, of course, what divided us.

My big dream remains a dream. Upon hearing Haitian-born University of the West Indies literature professor Marie-Jose Nzengou-Tayo recall her experience at the Caribbean Studies Association conference that May, I was inspired to try to do this on a smaller scale.

My big dream remains a dream. Upon hearing Haitian-born University of the West Indies literature professor Marie-Jose Nzengou-Tayo recall her experience at the Caribbean Studies Association conference that May, I was inspired to try to do this on a smaller scale.

I was motivated to document the stories that I had heard or heard about. So I sought them out. I wanted folks in Haiti involved but was only so successful as I found more availability among those of us in the diaspora who had more time for reflection.

The majority of the voices in Pawòl Fanm Sou Douz Janvye — the collection I edited — came from people who still had deep connections to family, friends and comrades in Haiti. What was most striking to me about these was the fact that contributors’ responses were as varied as their experiences.

The majority of the voices in Pawòl Fanm Sou Douz Janvye — the collection I edited — came from people who still had deep connections to family, friends and comrades in Haiti. What was most striking to me about these was the fact that contributors’ responses were as varied as their experiences.

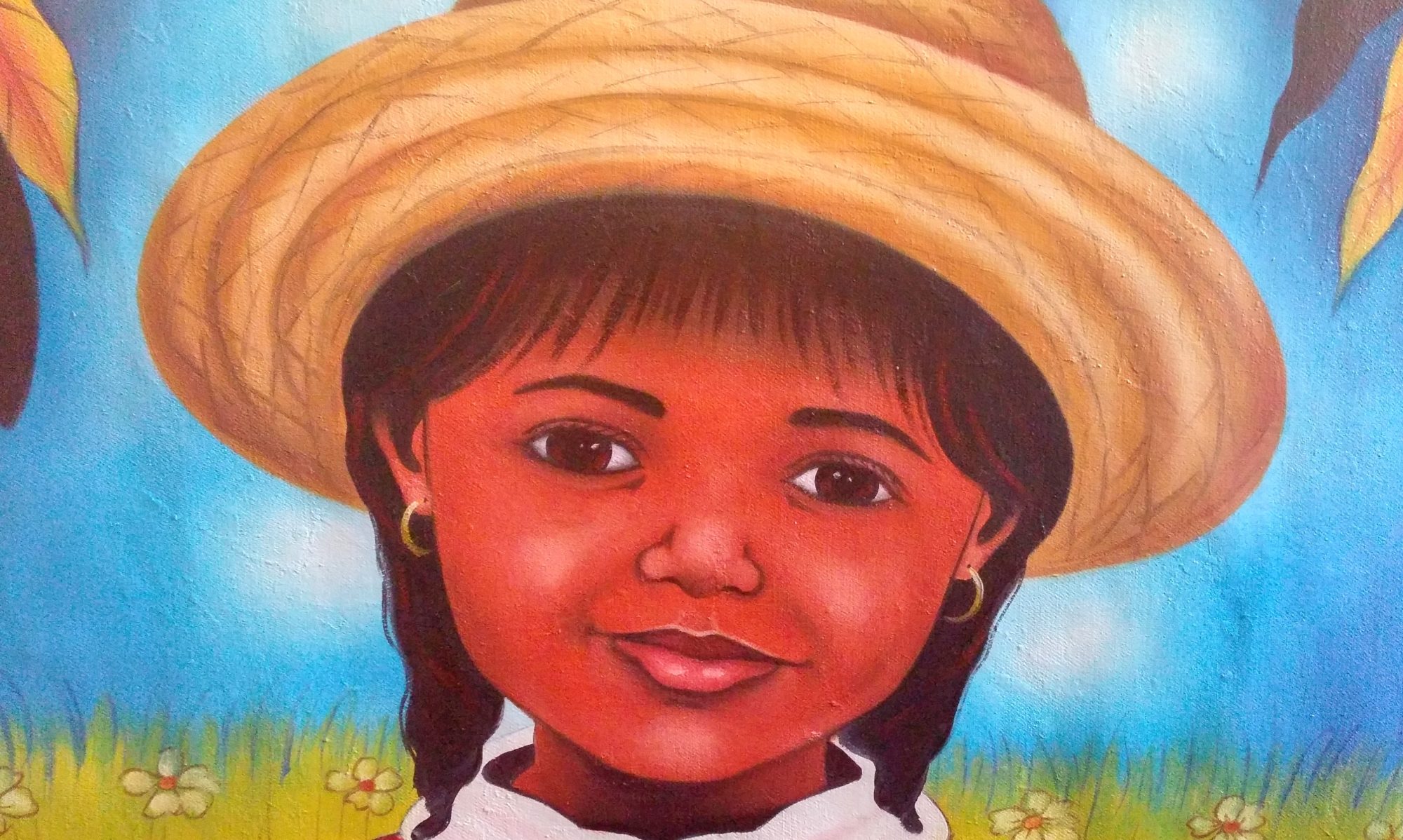

The tragedy had touched us at the core level right where expression begins. The ti istwas that ended up appearing in the journal came in many genres: essays, poems, first person narratives, letter, opinion pieces, fiction, and photographs.

They told us lots of stories about everything from the strong support that Haitians gave one another in the immediate aftermath of Goudougoudou. They also told us about the criminality of the mass graves, loss of family members, the hopeful yet frustrating medical missions, the adoptions, and life in the camps.

Not surprising, the content of these forms said as much about our differences as the media that we used. If only these differences could be truly seen and accepted for what they actually are: an indication that no matter how much Haiti is continually simplified, the experiences of its people both within and outside of it reflect an unquestionable truism– everyone has their own little story/history of Haiti. Haiti has always been and will always be plural.