We’re all connected. Yes. I’m not talking about Linkedin, Facebook, and other networking sites. We’re connected in the way that we’re not so different from one another. Dr. Maya Angelou, in her historic “Human Family” poem, puts it this way: “We are more alike, my friends, than unalike.” But what in the world could Dr. Angelou, MLK, President Obama, a new movement in Haiti called Kita Nago, and a certain Nadège Fleurimond possibly have in common? Come with me.

We’re all connected. Yes. I’m not talking about Linkedin, Facebook, and other networking sites. We’re connected in the way that we’re not so different from one another. Dr. Maya Angelou, in her historic “Human Family” poem, puts it this way: “We are more alike, my friends, than unalike.” But what in the world could Dr. Angelou, MLK, President Obama, a new movement in Haiti called Kita Nago, and a certain Nadège Fleurimond possibly have in common? Come with me.

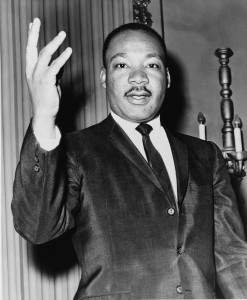

To say that Martin Luther King was just a guy who walked around (a lot), asking folk to treat one another fairly would be a transgression. Also, whether or not you voted for President Obama will never take away from the fact that he is not some dude who ‘tried out’ for president, and won. Twice.

We’re all part of the human family, but you’ve got to admit there’s something a little extra special about family members like Dr. King and President Obama. Don’t they seem to possess an extraordinary sense of. . .je ne sais qoui? People like that are beyond audacious and resolute in their mission. It’s almost as if they exist on a different plane.

Let’s step out of history books and ‘other planes’ for a minute. Zoom in on Brooklyn, New York. See that tomboy-at-heart lady in the pretty dress and uncomfortable high heels. Note how she scans the room to make sure everything is perfect. Here she is at so-and-so’s baptism, first communion, wedding, and a fancy event for some big-shot official. Her name: Nadège Fleurimond. What makes her more alike than unalike with. . . say. . .President Obama? Two words: Kita Nago (The ‘a’ sounds like alpha; the ‘o’ sounds like bravo).

Stay with me.

If you care anything about Haiti but have not heard of the Kita Nago movement, give it a little while. Kita Nago continues to sweep across our side of the island, gathering thousands of followers. “But what the heck is it?”

If you care anything about Haiti but have not heard of the Kita Nago movement, give it a little while. Kita Nago continues to sweep across our side of the island, gathering thousands of followers. “But what the heck is it?”

I read an interesting definition that included the words “mysterious” and “strange.” Ah, but that article has vanished from the Web. Now, that link takes you here. Not bad.

Others call Kita Nago a cross-like thing of mahogany that weighs close to a ton, which someone decided would make a great symbol for unity among Haitians. Thousands continue to carry it across the country. The destination is Ouanaminthe–a 430 mile trek from its place of origin, on foot! That’s roughly 17 back-to-back marathons.

People are confused by Kita Nago. Some are ashamed of it. Some are proud, and wish they could walk the miles with fellow countrymen. Some don’t like Kita Nago simply because of the words’ obvious connection to a certain ‘ancestral’ religion. One thing is clear: Kita Nago won’t stop until it reaches its destination. Google it.

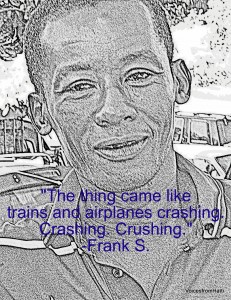

Get a thousand online definitions, but if you want to know what Kita Nago really means, find that elderly Haitian in your circle, Ask, Seek and Knock–ask. Our ‘granmoun’ elders carry volumes of this stuff inside their heads. Run and get those stories before the undertaker comes. In the meantime, here’s what my own Haitian mother told me:

When people say: “M pap fè yon pa kita, yon pa nago,” they mean “I am not moving. I am not taking one step from where I stand. You cannot make me move. I shall not be moved. I am resolute in my belief. You cannot unravel this faith in me. M pap fè yon pa kita, yon pa nago. Nothing you do can force me to alter my course. The dream I hold is my life-mission. No army will deter me from accomplishing it. M pap fè yon pa kita, yon pa nago.”

Now, focus your lens on a jail cell in Alabama not so long ago. See that man leaning on the bars? Can’t you hear Dr. King saying to himself: I shall not be moved. I will not relinquish this dream. No matter what they do to me, I will not abandon this mission. This movement is far bigger than I. They can kill me, but they cannot kill my dream. M pap fè yon pa kita, yon pa nago.

Now, focus your lens on a jail cell in Alabama not so long ago. See that man leaning on the bars? Can’t you hear Dr. King saying to himself: I shall not be moved. I will not relinquish this dream. No matter what they do to me, I will not abandon this mission. This movement is far bigger than I. They can kill me, but they cannot kill my dream. M pap fè yon pa kita, yon pa nago.

When President Obama ran for office the second time, Romney and Ryan wanted him to just go. Politely. They probably didn’t care where Obama went, as long as he abandoned the idea of being President of these United States. Again. Can’t you see Mr. Obama shaking his head? Can’t you hear him saying: No, no, not yet. I’m not leaving. I will not be moved. Or removed. ‘And I am telling you, I’m not going. . .’ M pap fè yon pa kita, yon pa nago.

Let’s go back to Brooklyn, New York. Don’t forget we are all more alike than unalike. Wait. Adjust the rear-view mirror. Go as far back as 23 years. (If you weren’t born yet, don’t worry; Google it.) Nadège Fleurimond was a 7 years old kid then. Her father had brought her with him from Haiti. No one said the words, but everyone knew the little girl would grow up to be a doctor. A lawyer. Something respectable. She would make the family proud. She would realize what they had not.

Adjust the rear-view mirror again. Look closer. It’s now 2003. There’s a grown-up Nadège in starched cap and gown. Diploma in hand–courtesy of Columbia University. It was not easy to earn that degree in Political Science, but she had done it. She was on her way to a smashing career as a. . .cook!

Adjust the rear-view mirror again. Look closer. It’s now 2003. There’s a grown-up Nadège in starched cap and gown. Diploma in hand–courtesy of Columbia University. It was not easy to earn that degree in Political Science, but she had done it. She was on her way to a smashing career as a. . .cook!

“You’re crazy!” her father had screamed. “You get that big degree, and all you want is to be a vending woman. You want to be a mashann like the ones on those filthy streets in Port-au-Prince? You want to waste your life? For all my sacrifice, you dreamed only of being a maid?”

“We rarely speak to each other now,” Nadège allows of her relationship with her father. It’s complicated. “He had his dream for my life; I had my own.”

Not everyone dreams about becoming a world leader, a poet, a teacher, a doctor, a lawyer, or whatever. “I want to be who I am,”Nadège continues. “And when the opposition gets to be too much, I believe in myself that much more.”

It’s been 11 years since Nadège fought to fulfill her dream. Fleurimond Catering is now a thriving business; she could not be happier. “I am not here to save the world,” Nadège explains with her infectious smile. “I take pride in bringing people together and representing my Haitian culture the way I know how. I follow my heart. We need to allow children to dream for themselves. When everyone tried to shake my dream out of me, I told them No. This is my path. I believe in myself enough to work for this. You can’t make me move. You don’t have the power to stop me. ”

It’s been 11 years since Nadège fought to fulfill her dream. Fleurimond Catering is now a thriving business; she could not be happier. “I am not here to save the world,” Nadège explains with her infectious smile. “I take pride in bringing people together and representing my Haitian culture the way I know how. I follow my heart. We need to allow children to dream for themselves. When everyone tried to shake my dream out of me, I told them No. This is my path. I believe in myself enough to work for this. You can’t make me move. You don’t have the power to stop me. ”

M pap fè yon pa kita, yon pa nago.