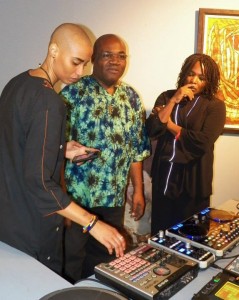

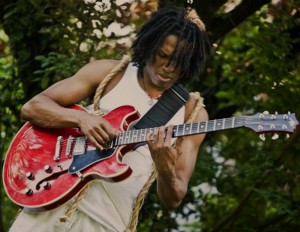

MONVELYNO ALEXIS‘s passion for music was fueled by a deep appreciation of the Gospel genre–which he credits for bringing awareness to his talent as a singer. “Music is the language of the soul,” Monvelyno says. “I want to speak it as well as I can. I want to have that conversation with everyone who wants us to understand one another.”

Monvelyno’s quest to speak “the language of the soul” took him to Soukri, Badjo, Souvnans–places which he calls “temples of Haiti’s musical legacy from our African ancestors.”

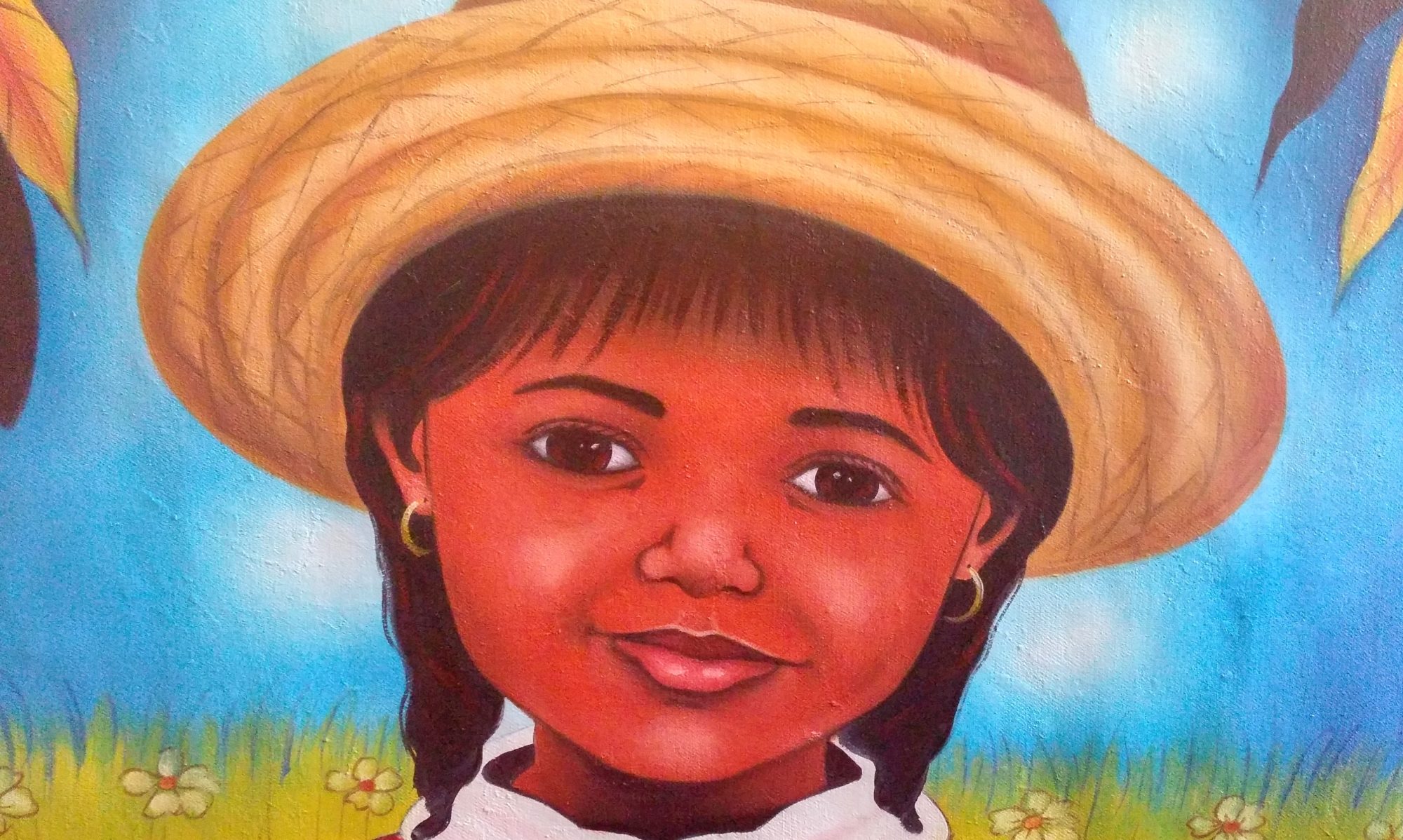

Those temples unlocked Monvelyno’s hidden potential and cleared new paths for his creativity. The idea of his Kòd ak Po (Strings & Skins) originated from conversations with vodun clerics and deep studies of their rituals and spiritual songs.

Monvelyno admits it will time and more projects beyond Kòd ak Po to continue to shape his studies into what the listener will discover as a major step toward a unique rendition of traditional Haitian music.”

I spoke to Monvelyno recently. The following is an INNERview into the man behind the sound: Meet Monvelyno Alexis!

Katia: I like the name Monvelyno. How did it become yours?

Monvelyno: My great-grandfather, who was from Brazil, loved the word Velyno. My father liked the sound of the word “Mon,” which in French means mine. They combined the two, and I became their Monvelyno.

Katia: That makes you your father’s son in a very special way. Were you born in Brazil as well?

Monvelyno: I was born in the Delmas section of Haiti. My dad had homes in Fontamara, yet our family never quite settled down. We move from place to place, as if we had nowhere to go. When I became conscious of what was happening; when I was no longer a kid; when I could process and understand things, I found myself in Carrefour Feuille. That was really the place where I grew up.

Monvelyno: I was born in the Delmas section of Haiti. My dad had homes in Fontamara, yet our family never quite settled down. We move from place to place, as if we had nowhere to go. When I became conscious of what was happening; when I was no longer a kid; when I could process and understand things, I found myself in Carrefour Feuille. That was really the place where I grew up.

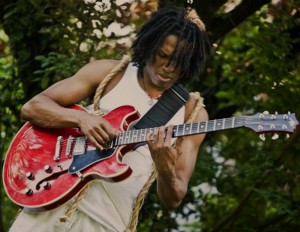

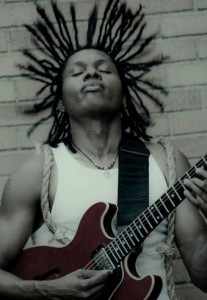

Katia: Did you always want to be a guitarist?

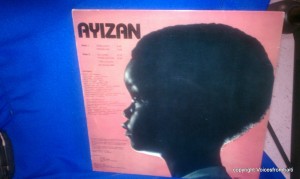

Monvelyno: Originally, I wanted to be a conga player. I love the drum. The instrument we call the guitar is not from my country. The conga is from my country. The core of my music is conga. When I’m composing, it’s the conga I hear. When I perform, I feel the conga. I grew up around bands like Foula with master percussionist Jean Raymond Giglio, who lived only for art and music. I’ll always mention his name wherever I go. Without Jean Raymond, I would not be half the musician I am today. Musicians like Bonga, Chico, Jean-Raymond, Samba-yo, and Tido introduced me to the treasure of Haitian traditional music. It’s only by chance that I play the guitar now. For a long time it was simply another means to express my thoughts and emotions. It’s different with the conga. The drum rhythms live inside of me: Congo, Nago, Ibo, Petro, Yanvalou. It’s only after I feel those rhythms that I pick up a guitar to find the chords, notes, that sort of thing.

Katia: What do you think of the generation of musicians coming up in Haiti right now?

Monvelyno: The new generation of Haitian musicians appears to be lost. They don’t seem to know what Haiti is about anymore. I am sorry to say this, but I think they have forgotten who they are. Music is a large part of our history. Culture is based on the history of a nation. If you forget your history, you’re not going to be able to express the culture. You’re going to be confused. You’re going to grab anything from anywhere and try to make it your own.

Katia: What exactly are they grabbing to make their own?

Monvelyno: They “borrow” mostly from American music. I went to Haiti recently and watched a music competition on TV. All the contestants sang American songs. Nothing was in Kreyòl. That made me sad. It’s really not the musicians’ fault, however. Haiti has suffered a lot. Outsiders have invested much in breaking down authentic Haitian culture. Some people really don’t want those kids to know who their ancestors were; they want them to forget their history and how they got here. The country is a mess, and the kids are products of that mess. Not to mention, the Haitian government invests very little in the arts. They don’t value artists. I became what I am because of the great people who surrounded me. Otherwise I would have been lost musically, too. I’d probably be trying to borrow from different cultures, too. I’d be trying to sing rap, too. We have a wealth of rhythms in our own culture. There’s no need to take what’s not ours. But the kids don’t want anything to do with traditional Haitian music anymore. That’s the reality of where we are.

Katia: Ultimately it is our fault. Are we the ones throwing away our own culture?

Monvelyno: Yes, in a sense. Few Haitian musicians are still dedicated to traditional music. When a country doesn’t value its own culture, it’s easy for the people to become lost.

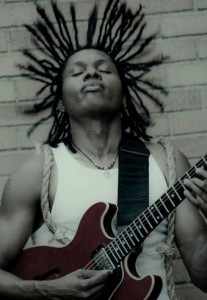

Katia: How would you describe what you do? Your music? Yourself?

Monvelyno: I want to show everyone the Haitian tradition. I want to show people how beautiful my country is. The music is not about me. We were, we are, and we will be a beautiful country. I carry that truth with me, and strive to express it in my music.

Katia: How long have you been living in the United States?

Monvelyno: I’ve been here for seven years. Before that I was in Martinique, Guadeloupe; I lived in Paris for some time. I traveled all over the place before I came to the United States.

Katia: Haitians at home call those who live outside the island a “Dyas.” How do you feel about that term?

Monvelyno: Dyas, to me, is a negative term. Those of us who carry the culture with us are more like ambassadors. It is true that when certain people come to the U.S., they don’t want to be Haitian anymore. I don’t want to put myself in that category. The ones who like to pretend they don’t speak Kreyòl anymore are probably the ones who deserve to be called Dyas. Me, I am Haitian wherever I go. I’m not carrying that Dyas label on my shoulder.

Monvelyno: Dyas, to me, is a negative term. Those of us who carry the culture with us are more like ambassadors. It is true that when certain people come to the U.S., they don’t want to be Haitian anymore. I don’t want to put myself in that category. The ones who like to pretend they don’t speak Kreyòl anymore are probably the ones who deserve to be called Dyas. Me, I am Haitian wherever I go. I’m not carrying that Dyas label on my shoulder.

Katia: What’s on your playlist right now?

Monvelyno: I listen to Foula. Samba-yo, Thurgot Theodat. Haitian musicians. Souvenance, Badjo, all the CDs that Aboudja made. That’s where I’m comfortable.

Katia: You love Haiti so much. Why do you live in New York?

Monvelyno: I am here because of circumstances. When you are a straight-forward artist, Haiti is not always the safest place for you. You might get arrested for speaking the truth. They put you in jail. They hunt you down. If I want to contribute and work for my culture, I have to be here for now. I can’t function in my country as a musician right now. But whenever I am there, I create like crazy. When I’m in Haiti I can compose at least 20 songs in just as many days. Our country is that powerful. If your mind and heart are in the right place, Haiti fills you with creativity.

Katia: I agree. When I’m in Haiti something in the ground reaches through me and fills me with inspiration.

Monvelyno: Exactly.

Katia: You said earlier that “straight-forward” musicians in Haiti are often hunted and not safe. And by straight forward, you mean those who don’t mask the truth of our daily reality. Do you think that’s the reason why upcoming musicians stay away from traditional Haitian music?

Monvelyno: Maybe. But the younger generation thinks anyone who plays Haitian traditional music is crazy. They’re into Jay-Z, Beyoncé, Rihanna, and Shakira. They want Haiti to turn into the US. Most of the young musicians in Haiti today don’t value our own culture. My first CD was completed 10 years before it was released. Nobody in Haiti wanted anything to do with traditional music. It took leaving the country for people to appreciate its worth. It was not possible to make that kind of music in Haiti.

Katia: If no one in Haiti wants to hear traditional Haitian music, what would motivate the new generation of musicians to take that route? What about money and being able to feed one’s family? Maybe the new generation of Haitian musicians—like the American artists they imitate—is just trying to make a living.

Monvelyno: Sure, money is great. If I played with those guys, I know I would make much more money than I do now. But those guys are not trying to keep Haitian culture alive. That is my personal mission—not chasing the dollar. I understand about making money. We have to eat.

Katia: Speaking of food: When you are hungry, do you reach for a hamburger or a plate of rice and beans?

Monvelyno: If you want to make me happy, give me my mayi moulen, my pitimi, yam. Give me my plantain with herring sauce. That’s want I want.

Katia: Is there a special person who cooks all this food for you?

Monvelyno: I cook for myself. When I invite friends to my house, I cook for them. That’s another way I share my culture with them.

Katia: Who taught you how to cook?

Monvelyno: My mother.

Katia: What else did your mother teach you?

Monvelyno: My mother gave me the basic knowledge of life. There’s no school that could have taught me what my mother did. My mother and my grandmother taught me everything I know is true and important.

Monvelyno: My mother gave me the basic knowledge of life. There’s no school that could have taught me what my mother did. My mother and my grandmother taught me everything I know is true and important.

Katia: Where are those ladies now?

Monvelyno: My mother is still in Haiti. She doesn’t want to be here. She says the cold weather would kill her. I don’t blame her. I understand.

Katia: You can’t argue against the sunshine. What are your thoughts about the rebuilding efforts taking place in Haiti today? Also, are they talking to the artists at all about their role in the new Haiti?

Monvelyno: They don’t consider us as important as the politicians, the doctors, the science people. Even teachers…they don’t consider teachers important at all. Musicians, artists (laugh). We’re going to lose large chunks of our culture. What is happening now should not be confused with re-construction anyway. It is construction. When you reconstruct something, you restore its original grandeur and beauty. That’s not what’s going on in Haiti today. They’re building a new country. What had been in the east now will be moved to the west. What had been in the south will go to the north. That’s building something new, not restoring what was there. It’s going to be like the original Haiti never existed. Authentic Haitian culture may be facing extinction. There will be a new culture when the supposed rebuilding is done, but it won’t be ours.

Katia: Monvelyno. If you could change one thing about Monvelyno Alexis today, what would it be?

Monvelyno: Go back to live in Haiti right now. That’s the only thing I would change.

____________________________

For Monvelyno’s concert schedule, please visit Reverbnation.

This exclusive VoicesfromHaiti INNERview was published previously in June 2011.

One very popular news article that’s been circulating about the Haitian Olympians contains a line that goes like this: “Four out of five of the Haitians at the Olympics have one thing in common: they’re not from Haiti.”

One very popular news article that’s been circulating about the Haitian Olympians contains a line that goes like this: “Four out of five of the Haitians at the Olympics have one thing in common: they’re not from Haiti.” How many are watching and cheering for Haiti’s team in London? Medal or no medal, we’re proud of them. Yes, we know that Linouse Desravine is the only who was born on the island. Perhaps we are impressed by more than her athletic prowess. Perhaps we’re just proud of people who choose to honor their ancestry in front of millions.

How many are watching and cheering for Haiti’s team in London? Medal or no medal, we’re proud of them. Yes, we know that Linouse Desravine is the only who was born on the island. Perhaps we are impressed by more than her athletic prowess. Perhaps we’re just proud of people who choose to honor their ancestry in front of millions. Pascale Delaunay, a sprinter, is disappointed about not making the team. This quote is from her blog: “I wanted to represent Haiti at the Olympic Games so that everyone could see Haitians are more than just poverty, I won’t be there but I have 4 great teammates Moise Joseph – 800m, Samyr Laine-Triple Jump, Jeff Julmis-110H and Marlena Wesh-200/400m) that I trust to represent our flag to the fullest.”

Pascale Delaunay, a sprinter, is disappointed about not making the team. This quote is from her blog: “I wanted to represent Haiti at the Olympic Games so that everyone could see Haitians are more than just poverty, I won’t be there but I have 4 great teammates Moise Joseph – 800m, Samyr Laine-Triple Jump, Jeff Julmis-110H and Marlena Wesh-200/400m) that I trust to represent our flag to the fullest.” Each one deserves a gold medal for standing, running, jumping, and kicking for our beloved country.

Each one deserves a gold medal for standing, running, jumping, and kicking for our beloved country.