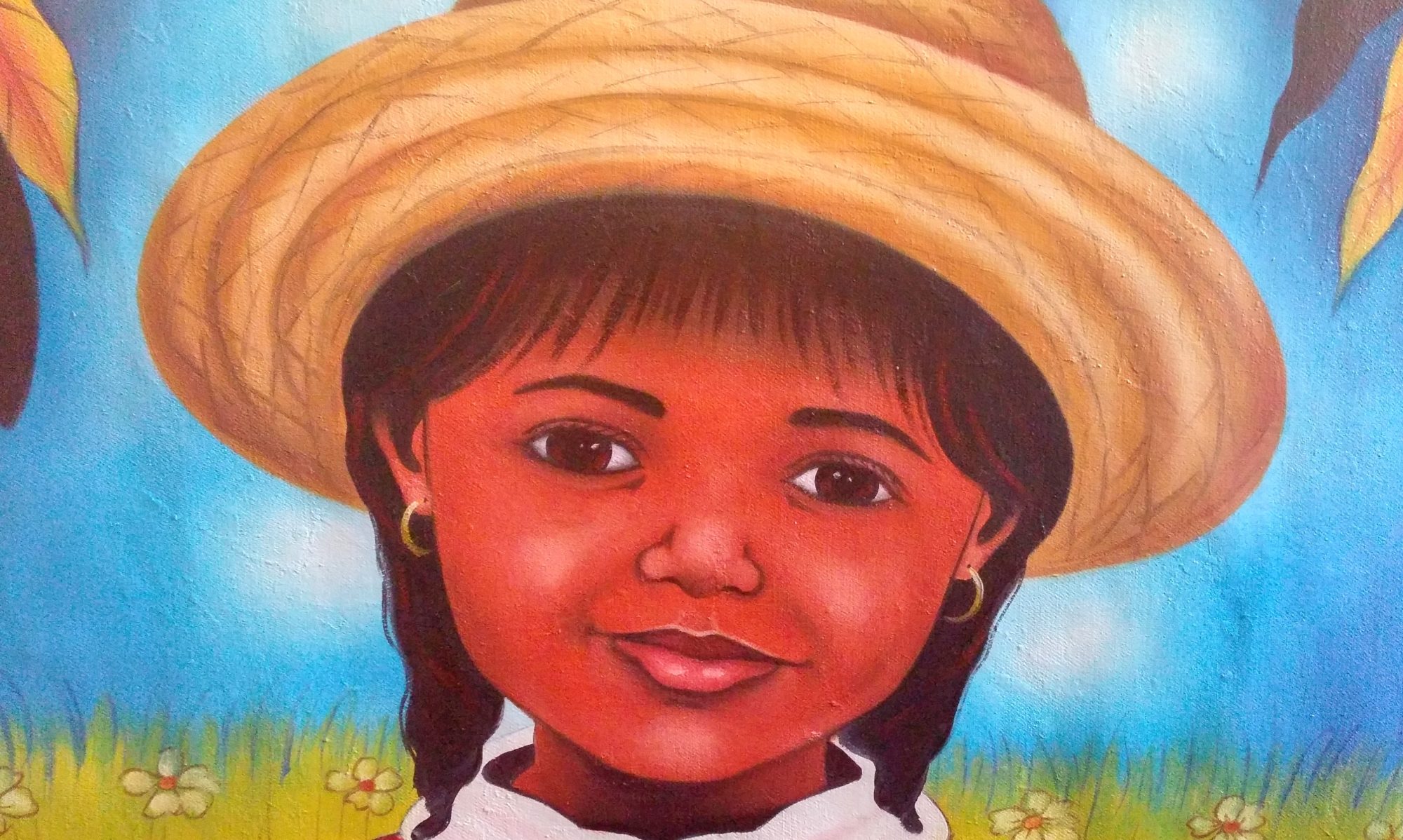

Jistis pou Roudline Lindor

There are some words that are impossible for this Haitian native to say in English.

Gen de pawòl ki enposib pou mwen, yon ayisyèn natif natal, di an anglè.

Gen de zafè ki pase sou tè sa a ki difisil pou moun ki gen konsyans konprann.

There are some things that happen on this earth that are difficult to comprehend.

Gen de moun ki pa merite yo rele yo ‘moun’; plis yo avanse lan sosyete, plis yo fè pa an aryè tankou vye bèt raje.

There are people who do not deserve to be called human. The more they advance as a society, the more rearward steps they take, like beasts in the wild.

Moun sivilize pa aji tankou lyon sovaj. Moun ki gen konsyans sipoze respekte lavi lòt. Menm si lòt moun nan se etranje li ye lan peyi w; menmsi nasyonalite lòt la se yon peyi ke w konnen nan fon kè w ou pa gen dwa janm ni sipòte ni renmen.

Civilized people do not act like savages. People with a conscience respect the life of others, even when those ‘others’ are strangers in your lands; even when the ‘others’ are of a country you know in your hearts you will never tolerate.

Douz Jiyè, lan dominikani, de bèt anraje efase lavi yon etidyan 20 an, Rooldine Lindor—yon ti moun inosan. Toupatou pawòl la pale.

July 12th, in the Dominican Republic, two enraged beasts erased the life of a 20 year-old student, Roudline Lindor—an innocent child, really. The news spread like a powerful flood–a category five hurricane, drowning our faith in mankind.

Zak sa a frape nou fò. Krim sa a afekte tout fi tout gason tout kote. Nou mande gras pou fanmi Rooldine. Nou mande jistis pou lavi ke bèt sovaj yo pran.

News of this monstrous crime hit us hard. People everywhere have been struck by this act of unmitigated violence. We pray that Rooldine’s family finds comfort. . . We demand justice for the girl’s abbreviated life.

San ayisyen dwe sispann koule gout pa gout lan dominikani.

Haitian blood must stop spilling in the Dominican Republic.

Vyolans de bandi yo fè kont Rooldine Lindor tèlman sovaj, moun toupatou oblije kanpe sou ran pou yo rele: Roudline se pitit nou tout li ye; se sè nou tout. Se fanmi nou tout.

The violence inflicted on Rooldine was so incomprehensible that people everywhere now stand in line to make their voices heard. The girl was our daughter. She was our sister. She was family.

Nou mete vwa-n ansanm pou nou rele sa se twòp.

We put our voices together to say Enough.

Li lè pou krim kont ayisyen sispann lan dominikani. Nou mande jistis pou fanm ak gason ayisyen k ap viv lan tout peyi etranje.

The time is now for crime against Haitians in the Dominican Republic to stop. We demand justice for Haitian women and men who live in foreign countries.

Lè w tande yon bèt devore yon lòt lan raje, nou pa di krik—sa se abitid bèt sovaj. Men lan moman nou ye la sou tè sa a. . . pou yon ti moun pa ka ale lekòl san li pa oblije gen senkant zye deyè tèt li, ka a grav pou lemond antye.

When we hear that a beast devours another in the wild, we don’t speak—that is the habit of animals. In these moments we live today. . .for a child not to be able to go to school without having fifty eyes behind her head. . .the situation is grave for us all.

Pou fanmi Rooldine Lindor, nou ofri kondoleyans ak tout kè nou. Pou lavi pitit fi dayiti sa a, nou mande jistis.

To Rooldine’s family, we offer our deepest condolence. For this girlchild of Ayiti, we demand justice.